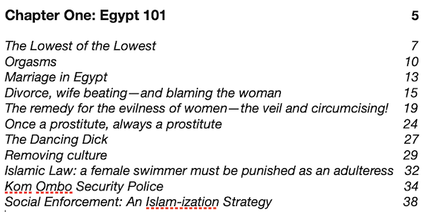

Pages 34-38 Kom Ombo Security Police

On the way to Kom Ombo for a field assignment we passed through a security checkpoint. Cars ahead of us would slow to a crawl before being waved on to pass. Occasionally someone was told to pull over for a more thorough check.

We slowed, were waved on, and made it through the checkpoint. My colleagues let out an audible sigh of relief. But suddenly there was yelling from behind us and a military officer, machine gun in hand, was shouting for us to stop. Our driver slammed on the breaks.

Three security officers approached and asked for ID and eyed my three companions in the front seat with great scrutiny. Two of the officers looked carefully at my passport, walked away and spoke to themselves for a moment, then returned and told me they knew who I was. They asked me several questions about where I'd be and for how long, then nodded and said, “Go."

After we pulled away and were out of earshot, my colleagues gave a loud hoot and a holler and gave each other a high five. A simple stop at a checkpoint can end up with a trip to the security police station and can last many exhaustive hours.

I am usually given a contact person for an assignment. This person is usually a sheik or a man who is trusted by the villagers. Most villagers in isolated regions would not like a foreigner filming their events and would not allow it if I did not have this person to pave my way.

For this assignment my contact was a sheik from a village in Kom Ombo. He brought a friend, the driver, and one family member to escort me to Kom Ombo. All three men sat in the front seat and I sat alone in back. The car was tiny, and they sat crammed in front, but none of them wanted to sit next to a woman.

The sheik's village consisted of large compounds where several related families lived. The compounds were fully enclosed with tall brick and cement walls and the only entrance was a padlocked metal door. You couldn’t see inside the compounds, or get in, without someone unlocking and opening the door. At one such compound, our driver got out, unlocked and opened the door, and I was ushered into a large courtyard.

Off to one side was a pigeon coop, plus other designated areas for animals and poultry, and an area for slaughtering with a table and waterspout. There were small doors lined along one long wall of the courtyard. Each door opened into a set of rooms where a family lived. I was invited into one of these rooms where seven women and five small children were gathered.

Women sat on the floor along the walls. There was no furniture. Even though this was a private, locked compound, six of the women were fully veiled in black with only their eyes showing. The other was heavily head-scarfed, the kind that hides the forehead and neck, and she wore a tent-like, mud-colored galabeya.

The women were all curious about me and each took turns asking me questions. Of course I got the usual questions about my marital status and children, but I was also asked what I liked about Egypt, what I didn’t like, what my favorite Egyptian songs were, and my favorite singers. And since I know Egyptian music and singers as well as any Egyptian, my selections made them happy, and many nodded in approval at my answers.

But then I was asked if I was a friend of Suzanne Mubarak.

This was a hard one. The First Lady and I had corresponded in writing about my work. She had even sent me a letter once via the Official Presidential Car, accompanied by Military Police, and it was handed to me personally by a member of her staff. This had given me fifteen minutes of fame in my neighborhood.

Yes, Mrs. Mubarak paved the way for me to work with the Ministry of Culture, but we are certainly not friends in the usual sense of the word.

Thanks to Mrs. Mubarak’s letters of recommendation, many Ministers and Vice Ministers in government knew who I was and I had met with several in person to discuss my work. There were many official documents in security and police departments all over Egypt allowing me into areas that foreigners aren’t allowed into, thanks to Mrs. Mubarak.

I had also been mentioned twice in the main Cairo newspaper for doing a research and documentary project in cooperation with the First Lady. Even the officers at the security checkpoint had known who I was, so what the heck, right?

I answered the question with a yes.

This seemed to impress a few of them. But most looked uneasy. Were these women resentful of the modern reforms Suzanne Mubarak was making regarding women? Reforms that they could not partake in, like removing the veil, or not being forced to live in a locked compound?

A few uncomfortably quiet moments passed, then someone let out a loud zaghareet, which is a shrill yodel-like sound done at weddings and other joyful celebrations. We all laughed and the tension broke.

After a few hours of socializing with women from other parts of the compound, a male relative arrived and escorted me out, locking the padlock on the heavy metal door as we left. It was then that I fully felt the impact of being locked inside, and only able to get out if a male came to let me out.

I was taken to a shaded area where the sheik was smoking shisha with a group of men. As I was introduced to each man, I was careful about shaking hands. In villages like these, some men will willingly offer their hands, others hold back. There are those who think touching me would be haram (evil/forbidden).

The sheik then took me to his compound. His compound was much better off than the previous one and he was obviously proud of it. He had more animals and a larger enclosed reception area. Like the other compound, there were many rooms designated for different families.

I was escorted to a large, central room where I met the elder male members of the family. One of the sheik’s brothers was sitting on the floor, leaning against a wall smoking hash. He was an obvious Muslim Brotherhood, complete with the short white galabeya, a long, untrimmed beard, and the purposeful scab on his forehead from rubbing it on the ground when he prayed.

Eventually children began bringing in platters of food. The sheik and his male relatives were proud to be feeding me, Egyptians are very hospitable. But as I ate I had a bad feeling. The meat tasted strange; it tasted off, not right. They had piled my plate full of it because meat is a big symbol of hospitality, honor, and affluence.

I always eat as much as possible when invited into people's homes because it means I accept their hospitality and appreciate their food. It’s a compliment if I eat a lot, so I did. Plus, the male who was an obvious Brotherhood member was carefully eyeing me. I did not want him to have any reason to hate me any more than he probably already did, as I represented everything he hated: I wore no headscarf and I was free to roam the country and work independently among males.

It had been a long day, so after eating I thought I’d better use the bathroom while I was somewhere where I could. We’d be moving to a festival soon, an outdoor one, so who knows what I could expect as far as a toilet. Probably none. I asked to use the hammam and the youngest adult male looked embarrassed and left the room. When he returned, he apologized and said it would be awhile because they had to “prepare it.”

While waiting, I watched as male children came in and ate the leftover food on our plates. After about a half hour I was escorted to the bathroom. It was the only bathroom in the compound. Since there were so many people living in this compound, I'm guessing they also used potty pots, or maybe had a designated outdoor area.

The bathroom I was taken to was the size of a small closet, just barely enough room for one body. It had a hole in the ground and a small water tap with a hose connected to it. There was no window or vent. The temperature outside was around 100 degrees, this tiny enclosure felt at least 150, and airless.

The bathroom had been rinsed down and water was still dripping from the ceiling and walls. Pieces of poop still stuck to the lower walls and floor. The odor almost made me lose it—and I am very tough.

When I came out from the bathroom, several of the men had gathered right outside the door. They had obviously come to see my reaction. Though their presence startled me a bit, I acted like all was well and that the bathroom experience was nothing new. Some sighed in relief and some nodded, and I noted that the Brotherhood member seemed almost disappointed. I think he was hoping my reaction would cause the others to think poorly of me.

After thanking everyone and talking a little with several of the children, who were in awe of my long blonde hair, we left for the “club.” That’s what they called it, but it was an open area in the center of the village.

A traditional band was tuning up and practicing a bit. A few chairs were placed in strategic spots for the dignitaries—the eldest males of nearby villages. All other males and male children sat on the ground. Women sat way off in an alley, kept totally out of sight. They would be unable to see the festivities about to take place, but would be able to hear the music.

As I walked by the alley where the women were kept segregated, I noticed that all the women were fully veiled, including gloves to cover their hands. Even toddlers, barely of walking age, were fully veiled. It was then that I looked around at the extremely large gathering of men and noted their clothing and the scabs on their forehead. The villagers were Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists.

The music started and a line of males began to do el-Kahf, a hand clapping dance. I had never gotten this type of el-Kahf on film before, so I was thrilled. Hand clapping as a rhythmic base came long before the invention of drums, so hand clapping dances are considered very ancient and handed down from one generation to another.

After about an hour of filming, I suddenly began to feel nauseated. I was pretty sure I had food poisoning.

This was a very big annual event. Leaders of local villages and important males from various villages were doing the dancing. We hadn't begun the most important part of the festival, but I was fearful I’d become more ill soon and might end up trapped in a locked compound (and spending most of that time in an odoriferous bathroom).

My usual assistant at the Ministry of Culture was also on a field assignment and was not answering his cell, so I called Essam. I needed a story to get me out of there fast. After speaking with Essam, the sheik ushered me to a car in one of the back alleys. We hit the road and made it out of the village and onto the dark country road.

But soon afterwards, were stopped by an unexpected roadblock with a large number of security police.

After looking at my ID and then making a quick call, they said they knew who I was. At first I thought this was good, they'd release us quickly. After my call to Essam, he had arranged a hotel room for me in Luxor, about 100 miles from the village I had been filming in. I was anxious to get to a bed—and a bathroom.

But the officers would not let us go.

Essam is the only Egyptian I’ve ever met who does not fear police, military, or any authority. This is probably because he is manager of a company owned by retired EIA (Egyptian Intelligence) and many of his friends from childhood are now generals in the army.

So once again I called Essam for help. After talking briefly, the officer handed the phone back to me. Essam said, “They are worried about your safety because there's been some terrorist activity nearby. They are going to escort you out.”

Moments later a military truck arrived, with two officers in the cab and six soldiers in back carrying machine guns. They kept close to our rear bumper for about an hour, until my military escorts felt I was safely out of the terrorist zone.

Note: Within a year after this visit, there were horrific attacks on the Christian villages in this area. Then later, after the Muslim Brotherhood took power, hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists surrounded the main church in Kom Ombo and burnt it to the ground. Christian homes and businesses were attacked for three days. In Luxor, too, horrific attacks on Christians took place.

On the way to Kom Ombo for a field assignment we passed through a security checkpoint. Cars ahead of us would slow to a crawl before being waved on to pass. Occasionally someone was told to pull over for a more thorough check.

We slowed, were waved on, and made it through the checkpoint. My colleagues let out an audible sigh of relief. But suddenly there was yelling from behind us and a military officer, machine gun in hand, was shouting for us to stop. Our driver slammed on the breaks.

Three security officers approached and asked for ID and eyed my three companions in the front seat with great scrutiny. Two of the officers looked carefully at my passport, walked away and spoke to themselves for a moment, then returned and told me they knew who I was. They asked me several questions about where I'd be and for how long, then nodded and said, “Go."

After we pulled away and were out of earshot, my colleagues gave a loud hoot and a holler and gave each other a high five. A simple stop at a checkpoint can end up with a trip to the security police station and can last many exhaustive hours.

I am usually given a contact person for an assignment. This person is usually a sheik or a man who is trusted by the villagers. Most villagers in isolated regions would not like a foreigner filming their events and would not allow it if I did not have this person to pave my way.

For this assignment my contact was a sheik from a village in Kom Ombo. He brought a friend, the driver, and one family member to escort me to Kom Ombo. All three men sat in the front seat and I sat alone in back. The car was tiny, and they sat crammed in front, but none of them wanted to sit next to a woman.

The sheik's village consisted of large compounds where several related families lived. The compounds were fully enclosed with tall brick and cement walls and the only entrance was a padlocked metal door. You couldn’t see inside the compounds, or get in, without someone unlocking and opening the door. At one such compound, our driver got out, unlocked and opened the door, and I was ushered into a large courtyard.

Off to one side was a pigeon coop, plus other designated areas for animals and poultry, and an area for slaughtering with a table and waterspout. There were small doors lined along one long wall of the courtyard. Each door opened into a set of rooms where a family lived. I was invited into one of these rooms where seven women and five small children were gathered.

Women sat on the floor along the walls. There was no furniture. Even though this was a private, locked compound, six of the women were fully veiled in black with only their eyes showing. The other was heavily head-scarfed, the kind that hides the forehead and neck, and she wore a tent-like, mud-colored galabeya.

The women were all curious about me and each took turns asking me questions. Of course I got the usual questions about my marital status and children, but I was also asked what I liked about Egypt, what I didn’t like, what my favorite Egyptian songs were, and my favorite singers. And since I know Egyptian music and singers as well as any Egyptian, my selections made them happy, and many nodded in approval at my answers.

But then I was asked if I was a friend of Suzanne Mubarak.

This was a hard one. The First Lady and I had corresponded in writing about my work. She had even sent me a letter once via the Official Presidential Car, accompanied by Military Police, and it was handed to me personally by a member of her staff. This had given me fifteen minutes of fame in my neighborhood.

Yes, Mrs. Mubarak paved the way for me to work with the Ministry of Culture, but we are certainly not friends in the usual sense of the word.

Thanks to Mrs. Mubarak’s letters of recommendation, many Ministers and Vice Ministers in government knew who I was and I had met with several in person to discuss my work. There were many official documents in security and police departments all over Egypt allowing me into areas that foreigners aren’t allowed into, thanks to Mrs. Mubarak.

I had also been mentioned twice in the main Cairo newspaper for doing a research and documentary project in cooperation with the First Lady. Even the officers at the security checkpoint had known who I was, so what the heck, right?

I answered the question with a yes.

This seemed to impress a few of them. But most looked uneasy. Were these women resentful of the modern reforms Suzanne Mubarak was making regarding women? Reforms that they could not partake in, like removing the veil, or not being forced to live in a locked compound?

A few uncomfortably quiet moments passed, then someone let out a loud zaghareet, which is a shrill yodel-like sound done at weddings and other joyful celebrations. We all laughed and the tension broke.

After a few hours of socializing with women from other parts of the compound, a male relative arrived and escorted me out, locking the padlock on the heavy metal door as we left. It was then that I fully felt the impact of being locked inside, and only able to get out if a male came to let me out.

I was taken to a shaded area where the sheik was smoking shisha with a group of men. As I was introduced to each man, I was careful about shaking hands. In villages like these, some men will willingly offer their hands, others hold back. There are those who think touching me would be haram (evil/forbidden).

The sheik then took me to his compound. His compound was much better off than the previous one and he was obviously proud of it. He had more animals and a larger enclosed reception area. Like the other compound, there were many rooms designated for different families.

I was escorted to a large, central room where I met the elder male members of the family. One of the sheik’s brothers was sitting on the floor, leaning against a wall smoking hash. He was an obvious Muslim Brotherhood, complete with the short white galabeya, a long, untrimmed beard, and the purposeful scab on his forehead from rubbing it on the ground when he prayed.

Eventually children began bringing in platters of food. The sheik and his male relatives were proud to be feeding me, Egyptians are very hospitable. But as I ate I had a bad feeling. The meat tasted strange; it tasted off, not right. They had piled my plate full of it because meat is a big symbol of hospitality, honor, and affluence.

I always eat as much as possible when invited into people's homes because it means I accept their hospitality and appreciate their food. It’s a compliment if I eat a lot, so I did. Plus, the male who was an obvious Brotherhood member was carefully eyeing me. I did not want him to have any reason to hate me any more than he probably already did, as I represented everything he hated: I wore no headscarf and I was free to roam the country and work independently among males.

It had been a long day, so after eating I thought I’d better use the bathroom while I was somewhere where I could. We’d be moving to a festival soon, an outdoor one, so who knows what I could expect as far as a toilet. Probably none. I asked to use the hammam and the youngest adult male looked embarrassed and left the room. When he returned, he apologized and said it would be awhile because they had to “prepare it.”

While waiting, I watched as male children came in and ate the leftover food on our plates. After about a half hour I was escorted to the bathroom. It was the only bathroom in the compound. Since there were so many people living in this compound, I'm guessing they also used potty pots, or maybe had a designated outdoor area.

The bathroom I was taken to was the size of a small closet, just barely enough room for one body. It had a hole in the ground and a small water tap with a hose connected to it. There was no window or vent. The temperature outside was around 100 degrees, this tiny enclosure felt at least 150, and airless.

The bathroom had been rinsed down and water was still dripping from the ceiling and walls. Pieces of poop still stuck to the lower walls and floor. The odor almost made me lose it—and I am very tough.

When I came out from the bathroom, several of the men had gathered right outside the door. They had obviously come to see my reaction. Though their presence startled me a bit, I acted like all was well and that the bathroom experience was nothing new. Some sighed in relief and some nodded, and I noted that the Brotherhood member seemed almost disappointed. I think he was hoping my reaction would cause the others to think poorly of me.

After thanking everyone and talking a little with several of the children, who were in awe of my long blonde hair, we left for the “club.” That’s what they called it, but it was an open area in the center of the village.

A traditional band was tuning up and practicing a bit. A few chairs were placed in strategic spots for the dignitaries—the eldest males of nearby villages. All other males and male children sat on the ground. Women sat way off in an alley, kept totally out of sight. They would be unable to see the festivities about to take place, but would be able to hear the music.

As I walked by the alley where the women were kept segregated, I noticed that all the women were fully veiled, including gloves to cover their hands. Even toddlers, barely of walking age, were fully veiled. It was then that I looked around at the extremely large gathering of men and noted their clothing and the scabs on their forehead. The villagers were Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists.

The music started and a line of males began to do el-Kahf, a hand clapping dance. I had never gotten this type of el-Kahf on film before, so I was thrilled. Hand clapping as a rhythmic base came long before the invention of drums, so hand clapping dances are considered very ancient and handed down from one generation to another.

After about an hour of filming, I suddenly began to feel nauseated. I was pretty sure I had food poisoning.

This was a very big annual event. Leaders of local villages and important males from various villages were doing the dancing. We hadn't begun the most important part of the festival, but I was fearful I’d become more ill soon and might end up trapped in a locked compound (and spending most of that time in an odoriferous bathroom).

My usual assistant at the Ministry of Culture was also on a field assignment and was not answering his cell, so I called Essam. I needed a story to get me out of there fast. After speaking with Essam, the sheik ushered me to a car in one of the back alleys. We hit the road and made it out of the village and onto the dark country road.

But soon afterwards, were stopped by an unexpected roadblock with a large number of security police.

After looking at my ID and then making a quick call, they said they knew who I was. At first I thought this was good, they'd release us quickly. After my call to Essam, he had arranged a hotel room for me in Luxor, about 100 miles from the village I had been filming in. I was anxious to get to a bed—and a bathroom.

But the officers would not let us go.

Essam is the only Egyptian I’ve ever met who does not fear police, military, or any authority. This is probably because he is manager of a company owned by retired EIA (Egyptian Intelligence) and many of his friends from childhood are now generals in the army.

So once again I called Essam for help. After talking briefly, the officer handed the phone back to me. Essam said, “They are worried about your safety because there's been some terrorist activity nearby. They are going to escort you out.”

Moments later a military truck arrived, with two officers in the cab and six soldiers in back carrying machine guns. They kept close to our rear bumper for about an hour, until my military escorts felt I was safely out of the terrorist zone.

Note: Within a year after this visit, there were horrific attacks on the Christian villages in this area. Then later, after the Muslim Brotherhood took power, hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists surrounded the main church in Kom Ombo and burnt it to the ground. Christian homes and businesses were attacked for three days. In Luxor, too, horrific attacks on Christians took place.

An American Woman Living in Egypt: Life during an Islamic takeover ~~ available at Amazon or order it from your local bookstore.